Anne V. Coates’ greatest cut in LAWRENCE OF ARABIA from this

Anne V. Coates’ greatest cut in LAWRENCE OF ARABIA from this

The pioneering film editor Anne V. Coates won an honorary Oscar after being Oscar-nominated five times. She cut Lawrence of Arabia, The Elephant Man, Chaplin, Erin Brockovich, The Eagle Has Landed and the underrated Unfaithful and Out of Sight. She worked with directors David Lean, Carol Reed, Richard Attenborough, David Lynch, John Sturges and Steven Soderbergh. Her first editing job was The Pickwick Papers in 1942 and her last was – at age 89 – Fifty Shades of Grey. In Lawrence of Arabia, when Peter O’Toole lights a match and blows it out, the match’s flame is cut into a magnificent desert sunrise; this has been called The Greatest Cut in cinema.

Among cinephiles, the prolific director Lewis Gilbert is probably best known for Michael Caine’s breakthrough picture Alfie (1966) and the art house hits Educating Rita and Shirley Valentine. But the versatile Gilbert also managed the Bond franchise’s transition from Sean Connery (You Only Live Twice) to Roger Moore (The Spy Who Loved Me and Moonraker). In his autobiography, Gilbert explained, “Roger didn’t have Sean’s animal grace. However, he was at ease in light comedy. It therefore seemed to me much more sensible for Roger to play to the strength he had, rather than the one Sean had”.

Claude Lanzmann was the director of Shoah, a work eleven years in the making. Describing Shoah as a “Holocaust documentary” fails to capture its significance as a work of art and of history. Shoah consists entirely of testimony from survivors, witnesses and perpetrators of the Holocaust, without any file footage or voiceovers. It’s over nine hours long, which is the longest film that any significant number of living humans has ever seen in a theater. I watched it on home video – not on a single sitting, but binging over a weekend. Its length has been criticized, but it’s only two hours longer than OJ: Made in America and three hours longer than The Best of Youth, both of which are eminently bingeable; I found the nine-hour viewing experience also imprints upon the viewer the vast scale of the Holocaust.

Bernardo Bertolucci, the Italian writer-director, is most renowned for The Conformist (1970), Last Tango in Paris (1972) and the 9-Oscar winner The Last Emperor (1987). The notorious Last Tango doesn’t hold up anymore, but I like Bertolucci’s latest work the best – The Dreamers and Me and You.

Cinematographer Robby Müller was endlessly groundbreaking. He pioneered use of fluorescent lighting in Wim Wenders’ The American Friend and then made the vast spaces of the Texas Big Bend country iconic in Wenders’ masterpiece Paris, Texas. He was also responsible for the one-way mirror effect in Paris, Texas’ pivotal peepshow scene. For better or worse, he jerked the handheld camera in Breaking the Waves. Müller gave a unique look to indie movies from Repo Man to Ghost Dog; The Way of the Samurai.

Penny Marshall was a front-of-the-camera star who moved behind the camera to direct. Forty years after Ida Lupino, this was still unusual; so, she was breaking ground for women working today. And without her, we woulnd’t have A League of their Own and “There’s no crying in baseball“.

Master screenwriter William Goldman adapted his own book for the sui generis and unforgettable The Princess Bride. His scripts included Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, All the President’s Men, Marathon Man and Chaplin. “Follow the money” in All the President’s Men was Goldman’s line.

Shinobu Hashimoto, the screenwriter for Akira Kurosawa’s masterpieces of the 1950s and 1960s, died at the age of 100. Hashimoto’s FIRST credited screenplay was Rashomon, one of the most original screenplays ever. He also wrote the samurai classics Seven Samurai, Throne of Blood and The Hidden Fortress, the humanistic drama Ikiru and the neo-noir thriller The Bad Sleep Well. Because of Seven Samurai, he also gets a credit for The Magnificent Seven and its remakes.

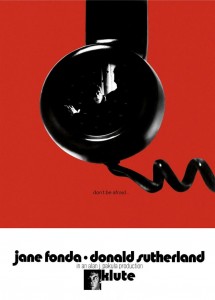

The master of the iconic movie poster, artist Bill Gold, died at 97. His first poster was for Casablanca. He followed that with hundreds of the most unforgettable poster images, including over thirty for Clint Eastwood movies alone. Here’s his poster for Klute.

For each movie, somebody has to design the title sequence. The best was Pedro Ferro, whose work spanned from Dr. Strangelove to Napoleon Dynamite. Here is his work on Bullitt.