I was delighted when Evil Does Not Exist finally trickled on to VOD recently. I had been eager to se it because of my admiration for it’s writer-director Ryusuke Hamaguchi, whose last movie, Drive My Car, made #1 on my Best Movies of 2021. Evil Does Not Exist had also won the Silver Lion at the Venice Film Festival. Unfortunately, I didn’t like it.

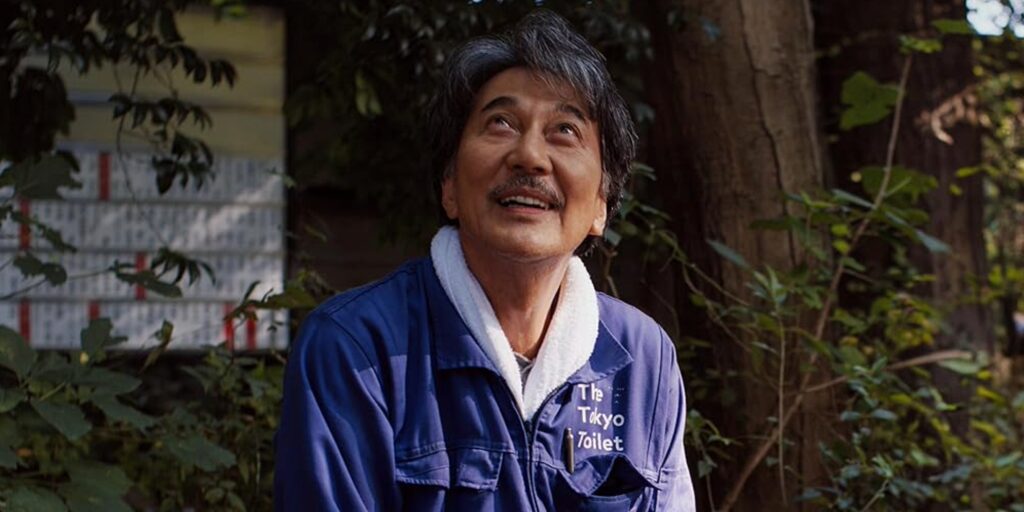

This parable is set in a tiny village nestled in remote mountains (shot near Nagano, Japan), with its surrounding forest still wild and relatively untouched. Takumi (Hitoshi Omika) is the village jack-of-all-trades, and he is attuned to the natural cycles of life in the forest. A hospitality corporation has bought land outside the village and hopes to attract tourists to a newly developed glamping camp.

Takahashi (Ryûji Kosaka) is the PR guy dispatched to sell the project to the locals and preempt any political resistance from them. When Takumi raises concerns at a community meeting, Takahashi smoothly tries to deflect them. However, Takahashi privately recognizes that Takumi is right – the project’s lack of adequate septic capacity will imperil the village’s drinking water. Takahashi is the most interesting character in the fil, as he takes risks to push back internally against the company line.

In a devastating ending, Takumi, who has been stewing about the water issue, reacts to an urgent situation by taking an action that was hard for me to understand.

Evil Does Not Exist has been described as mesmerizing, and that’s how I found the extended introduction to be, but but too many scenes are way too long, especially the community meeting. I’m more patient and receptive to slow burns than most movie viewers, but, IMO, this story needed to be told more economically. Then, the ending lost me.

Now, I’m an outlier here. Besides its slew of prestigious festival awards, Evil Does Not Exist has an 83 rating on Metacritic, including raves by some of my favorite critics.

Evil Does Not Exist is streaming on Amazon, AppleTV and Criterion.