The Brutalist opens with László (Adrien Brody) arriving in New York Harbor as a refugee. Emma Lazarus could have been thinking of László when she wrote her immortal poem; having survived Buchenwald, he is tired, poor, huddled, homeless and tempest-tossed.

He makes his way to Philadelphia, where his cousin Attila (Alessandro Nivola), has gone native, Americanizing his name, marrying a Catholic New Englander, and opening a small furniture store that he intends to build into a bigger enterprise. László, who was a architect of accomplishment and renown in prewar Hungary, has no such aspirations. László is grateful merely to be alive and away from war- and Holocaust-ravaged Europe and is content with even the least comfortable accommodations and the most menial employment. He does yearn for reunification with his wife Erzsébet and niece Zsófia, from whom he was separated years before in the Holocaust; they are alive, but in Soviet-controlled territory, and getting them to America will be difficult and complicated.

Just when László gets a taste of a promising situation, things don’t work out with Attila, and László finds himself homeless again. But then fortune smiles upon him – to an incredible, unpredictable and life-changing degree. Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), a local zillionaire, learns of László’s international reputation and commissions a monumental vanity project – one that will bring fame and wealth to László. The only downside is that Van Buren is extremely capricious, and László owes all of his new found comfort to him. Van Buren giveth, and Van Buren can taketh away.

It is an asymmetrical relationship. László is all about expressing himself through his architecture. Van Buren is a collector, and, like any of his collectible objects, Van Buren enjoys László as an amusement and as a marker of prestige. Van Buren’s dominance manifests in countless micro-aggressions, and, finally, in the most degrading way.

László rides this roller coaster alone until Erzsébet arrives with Zsófia. László can be prickly and his confidence is always teetering, but Erzsébet is smooth and comfortable in her skin. Erzsébet is stronger than László, and many times as resilient. She has been able to survive a Nazi death camp, escape from behind the Iron Curtain and make her way to the New World, all while protecting her vulnerable niece. Although physically wrecked by her ordeal, she is eager to resume her career as a writer and her role as László’s coach and cheerleader. Erzsébet intends to make her own destiny, and refuses to be buffeted by the whims of fortune.

No matter how highly valued is his talent, László gets the message that he is too foreign, too Jewish, and, ultimately, is unwanted by America. While that weighs on him, his experience with Van Buren becomes soul-crushing. How much is too much for the human spirit to endure? Can Erzsébet help László find peace and dignity?

The Brutalist is a sweeping story, told in three hours thirty-five minutes (with an intermission), and every second brims with artistic ambition. Director and co-writer Brady Corbet has acted in movies by Gregg Araki, Michael Haneke, Lars Von Trier, Ruben Ostland and Olivier Assayas, and he is aspiring for his own individualistic masterpiece. Corbet makes every shot visually impactful, and the score juxtaposes period pop standards with throbbing, droning musical cues, and even begins with an overture. Corbet risked making The Brutalist pretentious and self-important, but it never is. Almost everything Corbet throws at the screen works to tell the story and to enhance our experience.

The one thing that doesn’t work is the epilogue, set in 1980, when an adult Zsófia (Ariane Labed) gives a speech at an architectural conference that honors László with a retrospective. Zsófia explicitly connects the dots between László’s artistic themes with the horrors of experience. After such a momentous and vivid story, told with so much artistry and innovation, the epilogue is both unnecessary and a buzz kill. It reminded me of the finale of another great movie, Psycho, in which Simon Oakland plays a psychiatric expert who explains to us that, indeed, Norman Bates was suffering from a recognized mental disorder. But, if you swing for the fences, you are allowed the occasional foul ball.

The acting is exceptional, especially the three leads, who are each justifiably Oscar-nominated. Adrien Brody brilliantly takes us through László’s remarkably up-and-down journey, with its very high highs and very low lows. (BTW Nikki Glaser’s best joke at the Golden Globes was “Adrien Brody – two-time Holocaust survivor.“)

Similarly, the battle between Van Buren and László (or the one between the good Van Buren and the bad Van Buren) wouldn’t be enough without Erzsébet being so appealing and such a badass. Felicity Jones captures her grace and ferocity.

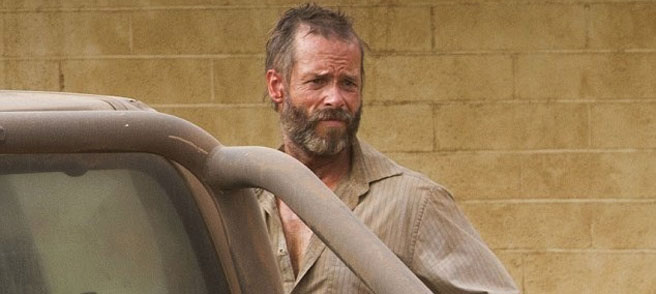

Much of the film relies on Guy Pearce’ Van Buren, whose appetites, prejudices, emotional needs and entitlement drives the plot, as they buffet poor László. If Van Buren isn’t complicated and unpredictable, there’s no story here. I find Pearce to remarkably resemble classic film star Brian Donlevy here.

The wonderful Ivory Coast-born, French actor Isaach de Bankole is as good as always as László’s American friend Gordon. Gordon often represents the moral center of the story, solidly grounded while László flutters about. Joe Alwyn is appropriately malignant as Van Buren’s rangy snake of a son, Harry Lee, to whom Harrison has not passed on any of his better qualities.

The Brutalist is an epic in several senses of that descriptor, and one of the Best Movies of 2024.