I’ve always enjoyed Noir City, the Film Noir Foundation’s flagship film festival, but I found the 2024 version to be especially rewarding. My attendance is usually driven by the opportunity to see films that are new to me, and those which aren’t available on VOD or even DVD. I particularly value being introduced to international noir, as I pointed out in my Noir City preview

It’s also great to hear the films introduced by film scholars Eddie Muller, Imogen Sarah Smith and Alan K. Rode. The 600-seat Grand Lake Theater, a period movie palace, was packed for each of the double features that I attended.

I experienced six films at this fest – two from France, two from the UK, one from Japan and one from the US – and four were new to me. They were:

- The Asphalt Jungle (US, 1950): Muller and Smith pointed out that the Production Code had banned filmmakers from depicting the means of committing crimes. So John Huston and the team behind The Asphalt Jungle blasted right through that stop sign in showing the intricate planning and execution of the heist. Those aspects and the assembly of the heist team are familiar elements of every heist film since, but they were completely original in The Asphalt Jungle. This film is especially well-cast (Sam Jaffe, Sterling Hayden, Louis Calhern, Jean Hagen, James Whitmore, John McIntyre and a 23-year-old Marilyn Monroe), but this time, I especially noticed the sparkling performances of supporting players Brad Dexter and Marc Lawrence.

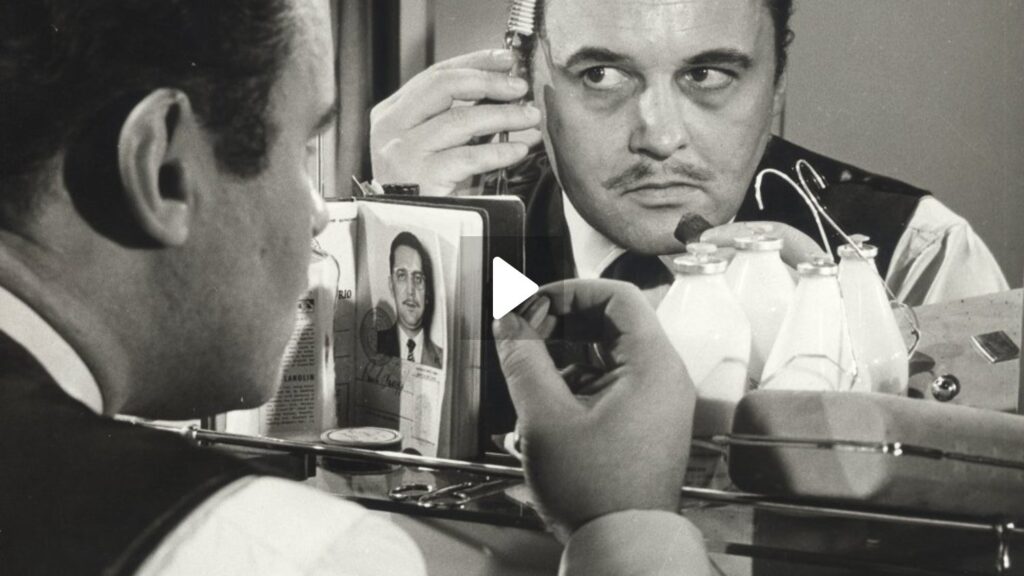

- Symphony for a Massacre (France 1963): Five crooks plan a big drug score that requires a large amount of capitalization, which will tap most of them out. They collect the fortune, send off the bag man and, then, one of the five steals it all. Each of the crooks becomes a detective trying to recover his money; of course, one of them is only pretending to look for the loot. It looks like the perfect crime, but there’s a slip, a surprise, another slip and…. Symphony for a Massacre is an early career showcase for Jean Rochefort, who plays a particularly amoral character with a reptilian smugness. Co-writer Jose Giovanni, who plays one of the crooks, knew crooked ways from his own eleven years in prison (and was concealing an even darker past). This is a top notch noir, and, because it is available for streaming, I’l be featuring it soon on this blog.

- Elevator to the Gallows (France, 1958): I’ve written about Elevator to the Gallows and its groundbreaking aspects, but it was such a pleasure to watch it on the big screen with a sellout crowd.

- Across the Bridge (UK, 1957): The ever-intense Rod Steiger is All In as a German-born British merger-and-acquisition buccaneer who is in NYC to gobble up a couple more companies when he learns that Scotland Yard is examining his books. He knows that, within a week, his three billion pound fraud will be discovered (and that’s in 1957 money!). He goes on the lam, figuring that he can travel incognito on the two-day train trip to Mexico and slip across the border before anyone is looking for him. He has money stashed in Mexico City that will buy him time to find a more permanent, extradition-free new home. But the news breaks while he is on the train, so he switches identities with a fellow passenger. His new phony identity brings a very unwelcome surprise. Steiger’s character is a brusque bully, used to getting his way. Usually in film noir, we’re rooting for the anti-hero to get away with it, and that’s not exactly the case here, but Steiger makes his financier’s predicaments and his attempts to evade them absolutely VIVID. The film’s director, Ken Annakin, observed that Steger was “trying to out-Brando Brando”. The story becomes a faceoff between Steiger’s fugitive and the corrupt Mexican police chief (an excellent Noel Willman). Oh – and there’s Dolores, one of the greatest three dogs (with Monty and Asta) in film noir. This is a first class movie, but a bit of a Lost Film, not available on VOD.

- Zero Focus (Japan, 1961): This is a dark mystery story with a woman’s focus; in fact, the three most pivotal characters turn out to be women. A man disappears, and his new bride, with some unreliable assistance from his employer and the cops, tries to find out what happened to him. Secrets are revealed, Rashomon-like, at the end , when the mystery is “solved” in differing ways by the police and, then, by two of the women characters; (the screenwriter also wrote Rashomon). The setting is a bleak, wintry coast. I found Zero Focus a little too long and talky at the end, but otherwise an excellent noir,

- The Strongroom (UK, 1962): The premise in this 74-minute British programmer is that the crooks easily rob a bank, but then realize that they’ll swing for capital murder if the bank employees now locked in the airtight vault succumb. In a race against time, the robbers try to break back into the bank – and it’s much harder the second time. There’s a shockingly abrupt, but satisfying, ending. Most of the audience recognized an actor playing one of the hoods, Darren Nesbitt, who went on to be a character actor in such memorable 1960s fare such as The Blue Max, The Prisoner and Where Eagles Dare.

Bottom line: Noir City revealed two hitherto unknown classics: Symphony for a Massacre and Across the Bridge. I’ll be writing more about each of them.